Journey of a seed

In the first of two articles about propagation, Penny talks us through selection, seed collection and germination at Westonbirt.

Why do we propagate seeds at Westonbirt?

Primarily to maintain and enhance our collection of trees as a Grade 1 listed landscape. We select the seeds to propagate from some key groups, these include; trees with heritage and historic value; those that fall within our National Collection of maple species, Japanese maple cultivars, lime species and all the hardy members of the walnut family; and species that are of interest for conservation, education and research reasons.

"We look to maintain and enhance the tree collection so future generations can enjoy it."

How do you choose which seeds to propagate?

We have an accession policy that determines the seeds we collect. Our database tells us how many of each tree species we have in the collection, when they were planted and how many are from a wild collected source. I work with our Curator, Mark Ballard, and Dendrologist, Dan Crowley, to decide which seeds are high priority. For example, we recently identified cedar of Lebanon (Cedrus libani) as a species we need to increase. It’s a signature plant and we only have six in the collection, the last of which was planted in 1961, so it's become a priority.

Forest Research Scientist, Matt Parratt, wading through a mountain stream. Seed collecting in Italy was not for the faint hearted with plenty of mountains and ravines to navigate!

Where do you find the seeds?

I only use UK collected seeds for growing rootstocks but other plants are propagated asexually or by cuttings, grafting or layering. We also make trips abroad to collect specific seeds. We recently made a trip to Italy to pick up species and subspecies that we don’t have in the maple collection. This included two important species, Acer opalus subsp obtusatum, a new introduction to the collection and Acer lobelii, which is rare in cultivation as all plants come from one known clone.

Do you just collect seeds and take them back to Westonbirt?

If only it was that simple! No, once we’ve identified the species we want we then obtain permits from the country of origin. The permit lists the organisations involved in the trip and those that the seed or resulting plant can be sent to.

"As well as collecting the seeds on our field trips, we also record all the details from the seed collection such as the altitude it grows at, longitude and latitude, associated species that it grows with and any other data that adds to our knowledge of the species and helps us to choose planting sites with the right conditions."

So the permits only allow specific organisations to receive seeds or plants?

The permits conform to The Convention of Biological Diversity and the Nagoya Protocol (when it’s agreed). The permit prevents plants from being distributed without control. For example, a tree may be found to have a value in a new medicine. Without controls that plant could simply be propagated by a corporation rather than the country of origin being able to benefit from their own natural resources.

How do you select the best seeds?

We do viability checks in the field. At the most basic level we check seeds for any sign of pests or disease. We’ll usually cut a selection of seeds open to check for a live embryo inside and a nice white moist flesh. There's a whole range of other tests that can be undertaken depending on the situation. These include: float tests, selecting only those that sink; test sowing of a batch to ensure they germinate in adequate numbers; biochemical staining using triphenyltetrazolium chloride that shows a reddish stain on live tissue; and X-raying seeds that have been soaked in heavy metal salts and photographed.

Seedlings propagating under Penny's watchful eye

Is it easy getting the seeds to germinate?

For some yes. Acorns are a good example of a simple seed to germinate. Most seed is covered with a 3mm depth of Horticultural grade grit that has been washed to remove traces of lime. As a general rule, they’re sown one and a half times their diameter apart and under that depth of grit. There are some seeds that don’t need covering, such as rhododendron, but care needs to be taken to keep the seed moist.

Other seeds need more attention to trigger them from dormancy. There are different types of dormancy but to keep things simple let’s just use physical dormancy as an example. This is when a seed remains dormant for a physical reason, the most common of which is a hard seed coat. Treatments could include: mechanical stratification, cracking, shaving or chipping the seed to improve its permeability to water and air; soaking in warm or cold water depending on the seed; and warm or moist scarification, often using peat or sand and then keeping the seeds at specific temperatures and in carefully monitored conditions that mimic their native environment.

Fruit dispersal

Trees have developed different ways of protecting or spreading their seeds. Here are a few examples:

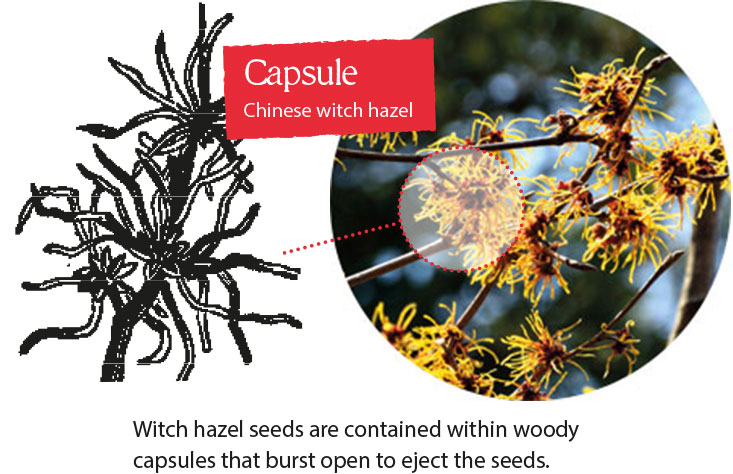

Capsule

Example: Hamamelis mollis (Chinese witch hazel)

Cone

Example: Abies alba (European silver fir), conifers generally

Conelet

Example: Alnus cordata (Italian alder)

Drupe

Example: contains a single seed and can be dry as in Halesia carolina (Snowdrop tree) or fleshy as in Daphne mezereum (Mezereon)

Fleshy

Example: Sorbus commixta (Japanese rowan) berries/drupes/pomes

Follicle

Example: Magnolia acuminata (cucumber tree)

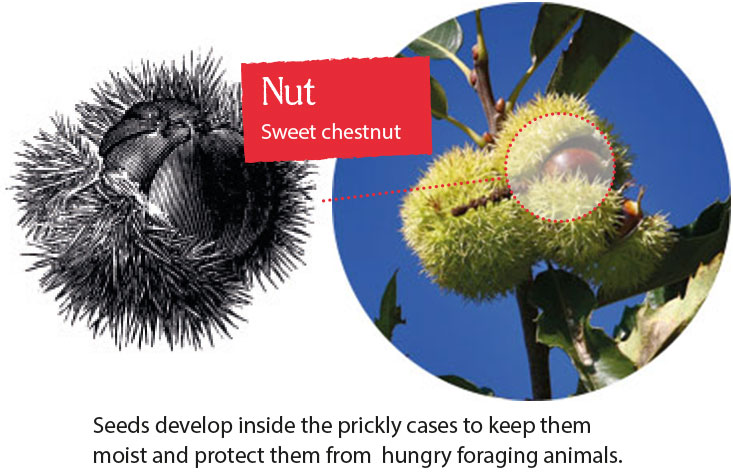

Nut

Example: Castanea sativa (sweet chestnut)

Nutlet

Example: Carpinus betulus (hornbeam)

Pod

Example: Robinia pseudoacacia (false acacia)

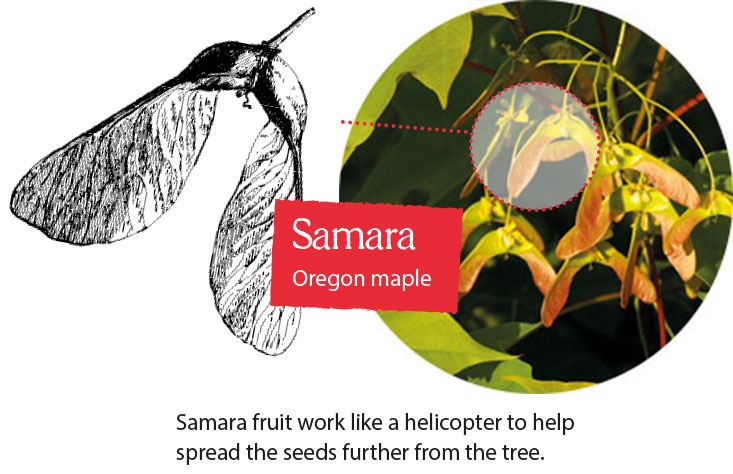

Samara

Example: Acer macrophyllum (Oregon maple)

Thanks Penny, we’ll catch up again in the summer edition to find out about your growing techniques and learn a bit more about all the growing houses and polytunnels!